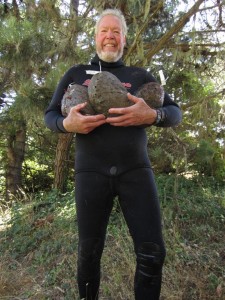

Jack Likins is an experienced abalone diver. He often gets trophy-size abalones, abalones that are ten inches or more. Here is Jack with a limit of ten inch abs.

He wrote this piece for the Independent Coast Observer and I thought it should also be shared here. Jack says if one death can be averted then the article was worth his effort. And if, like me, you will never dive for abalones, Jack's story will give you an idea of what it takes to do so.

Why Do Abalone Divers Die by Jack Likins.

I thought I’d take a stab at trying to explain why divers die abalone diving.

I've been abalone diving for over 50 years in both Southern California and here on the North Coast. It can be a very dangerous sport if not done with proper training, conditioning and knowledge of the ocean. Let me explain why.

From what I have observed, most of the deaths come as a result of what the newspapers call a "medical emergency". In other words, the deaths occur not directly from drowning but from some other medical problem (usually a heart problem) that may lead to drowning.

Think about it this way... A person who dives once or twice a year comes to the coast with his/her family and friends for a little diving and a lot of fun. If they have dived before they begin to get excited about the prospects of diving and getting abalones for a meal or to take home. If they haven’t dived in a while or kept swimming over the winter, they may not be in very good condition and many divers are older (50+). In any case, anyone will have anxiety and apprehension on their first dive of the season (it still happens to me and every diver I know). They look at the ocean, but they don’t have enough experience to know if the conditions are within their personal capabilities and they see other people and their friends diving so they think it must be OK. It’s difficult to say you don’t feel comfortable going into the water when your dive buddies all say they want to go. Who is going to be the one who backs out first? Ten years ago it was not going to be me. Anxiety probably causes most of these so called “medical emergencies”.

Here’s what happens. You put on an old wetsuit that may have gotten a little smaller over the years and it is very constrictive. It’s tight on your chest and gives you that claustrophobic feeling of confinement. As you start to suit up you start to thinking about sharks, even though the chance of being bitten are extremely rare, you can’t stop thinking about how it would be to be attacked by an 800 pound great white shark.

Once you’ve struggled to get into your wetsuit then you put a 20-30 pound weight belt around your waist, grab all your other gear (float tube, mask, fins, snorkel, ab iron, etc) and start walking to the beach (maybe down a cliff with a rope). By the time you get to the water you are sweating profusely from hiking in your wetsuit.

After putting on the rest of your gear you jump into 47-degree water and all of a sudden the cold water starts to seep into your wetsuit and you begin to swim, hard, to get out beyond the breakers. Maybe there is a current, maybe there are waves, maybe you start to get sucked out to sea and try to swim against the current, or maybe you just get knocked down by a wave and washed into the beach or rocks.

But, let's assume you are successful in getting out to the area where you want to dive and the visibility is only 2-3 feet underwater. You can't see the bottom, so you get out your underwater light. Since you can’t see the bottom from the surface, you dive down 15-20 feet and finally see the bottom, but it is covered with palm kelp so you have to go another 2-3 feet and get under the palm kelp. Once there, it is even darker so you shine your light to look into the rocky crevices and under the rocky ledges where the abalones live.

Now you've successfully gotten to the bottom and have looked for abalone, maybe even found one and you want to go back to the surface. You can’t use any type of underwater breathing apparatus so you have to be constantly going down and up as you look for abalones. When you decide to return to the surface you look up and the surface is covered with matted bull kelp, so you look for the light shining through the kelp and head for a clearing hoping not to get tangled in the long strands on your way to the surface.

Let’s say you dive for 45 minutes to an hour. You’re getting tired and now its time to head back to shore, but the wind has picked up during that hour and there is a current running in the opposite direction that you want to swim. Maybe the waves have picked up too, maybe the tide is lower and the exit is more rocky. What do you do? Hopefully you’re in good enough shape that you can swim against the current, or you have a “bail out” location down current where you can safely get out of the water.

If you’re lucky or experienced and have planned right, you will get back to shore safely. I am trying not to exaggerate, but I have had all of these things happen to me at one time or another. Now imagine thousands of divers, many of whom are not very knowledgeable or experienced and you can understand how some of them become overly anxious and why 3-4 people die every year.

If you’re lucky or if you are well trained and experienced you can avoid these hazards of abalone diving and get safely back to the beach with an abalone or two to enjoy with your friends and family. If not, from what I have described, you can understand how this sport can be deadly. Personally, I would not want to stake my life on luck. I’d rather base my life on knowledge and experience.

My advice… the best way to prevent these hazards is to avoid them altogether. In other words, don’t dive if you don’t feel comfortable with the ocean conditions, even if your dive buddies want to dive. If you dive or have friends who dive, the best advice you can give them is “don’t go into the water when the conditions are beyond your capabilities”. To be able to judge ocean conditions you must have the knowledge to “read” the ocean and the experience to understand your own capabilities. To me, this is what the buddy system is all about. If you are a new or inexperienced diver, find an experienced buddy who can help you gain the knowledge and experience, both in and out of the water, and one that won’t push you beyond your comfort level.

Having said all this, if you pick the right day with the right conditions and don’t push beyond your ability, conditioning and knowledge then abalone diving can be a wonderful, eye-opening experience. Most of the time I go abalone diving I don’t ever take an abalone, although I see hundreds of them. What’s most rewarding to me is the experience and the wonders of the ocean that I see every time I dive. More often than not, I will see something that I have never before seen. The ocean is an amazing environment and one that has only begun to be explored and understood by man.

I thank Jack for allowing me to share his story and photo with you here.